I recently had the pleasure of being interviewed by Phil Robinson for a piece in The Times around mental health apps and my own experience of working for and using Buddy in my own treatment. Here is a short extract from the piece – you can find the full article linked to at the bottom of the post.

Phil Robinson,

I was staying at a five-star hotel in Greece when I broke down. I couldn’t move or speak; I wept for no reason. So I was flown home, diagnosed with depression and sent to a private psychiatric hospital, where therapists began rebuilding my mind.

For weeks, with groups of almost broken, funny, and desperate humans, I attempted to learn the tenets of cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT). I didn’t want to be stuck in a room with a bunch of people who had, like me, flunked life, but it saved me. Beyond anything that was said in that room, I was sure that I wasn’t alone.

For people suffering from depression today, access to therapy is no longer a foregone conclusion. But whatever your problem — paranoia, body dysmorphia, BPD, OCD, PTSD — there’s probably an app for it. And this month, the health and life sciences minister George Freeman launched a £650,000 innovation prize to promote the creation of a new generation of mental health software.

So far there are 26 apps (11 are free) recommended by the NHS as part of a drive to automate healthcare, relieve waiting lists for talking therapies and reduce the £100 billion that it spends on treating mental health patients every year.

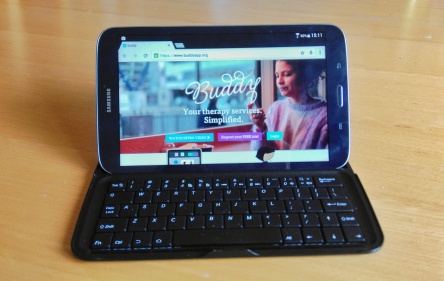

One, called Buddy, has been used by 12 NHS trusts and has been used by more than 17,000 people. An SMS and browser-based diary and communication tool, it’s designed to be used in conjunction with seeing a therapist, says Kat Cormack, who is Client Director of Buddy but also uses it “in my own treatment”.

I get a daily text from Buddy,” she says. “‘Hi Kat, Buddy here, how are you doing? Rate your day from 1 to 5 and tell us how you feel!’” As well as rating her state of mind, she can add notes. “It’s connected to my clinician, so I can tell her things that I might not be able to say looking her in the eye. I can confess my darkest secrets.

By analysing the data, a clinician can monitor a patient’s progress or use it to aid diagnosis. She cites a woman whose long-term depression was revealed to be hormonal after her Buddy data was found to correlate with information from another app tracking her menstrual cycle. “She changed her medication and is now free of depression for the first time in decades.”

When I was being treated for depression in the Nineties, I saw my therapist once a week, my psychiatrist once a month. I can see that apps present an opportunity to collect evidence to hasten recovery, yet the ability of most apps to deliver a quality service to vulnerable people remains questionable.

Away from the NHS’s recommended apps page, there are thousands of apps dealing with every condition. In most cases their publishers are as obscure as the evidence of their clinical efficacy. At one end of the spectrum you have apps such as MoodKit, the product of the experience of two respected doctors; at the other you have apps such as Fukitol, which is named after a Robin Williams joke.

The industry is still in its infancy and evidence from clinical evaluation trials is scarce. However, in 2013, a study of Viary, a Swedish app for depression, found that 73.5 per cent of patients who used the app were no longer considered depressed after eight weeks and needed half as many therapy sessions as those who engaged in therapy without it.

The result offers a glimpse of why these apps have been seized on as the holy grail of mental healthcare: promoted as a form of triage, they enable health services to push users to take responsibility for themselves and to cut face-to-face therapy.

Cormack is aware that digital tools such as hers are used by people who are frantic for NHS counselling but have not received it.

The waiting list for an assessment can be up to a year. That’s why people are using apps — they are either a stopgap when you are on a waiting list, or if the NHS has told you that you don’t meet their criteria. People get desperate. We are losing lots of low-cost counselling services because they can’t survive in this financial landscape

When I was at my lowest, between 1998 and 2002, it was always possible to see a counsellor at my local surgery. In 2015, a GP refers people like me to IAPT, an acronym for the suspiciously titled “Improving Access to Psychological Therapies”. It’s a stepped care program that begins with an assessment by phone from a “psychological wellbeing therapist”. Those assessed to have a condition that is interfering moderately with their lives are given a computerised CBT course to complete at home.

If this magic bullet fails, they are given self-help options, or signed up to a 100-person psychoeducation class (like speed awareness courses for people with depression). If you still stubbornly fail to regain your mojo, you can join a year-long waiting list for talking therapies, during which time you can use one of the many apps. The hope throughout this process is that patients simply disappear from the waiting lists as cured, or over the worst of it.

Therapy via healthcare app might seem like treatment purgatory, but anecdotal evidence from practitioners suggests that apps for depression and anxiety work particularly well with certain sectors of the population, such as the military and teenagers, who are notoriously reluctant to talk about emotions.

This is just an extract, the full piece on The Times website (subscription service).